This period of isolation has allowed us at Pineapple Gallery to reset and to re-evaluate our priorities, to daydream and to also think about some of the artists we celebrate in our Collection of Cult Art Prints. We wandered what their life offered them, as artists of the past living through various restrictive conditions, & we imagined small parts of their life experiences.

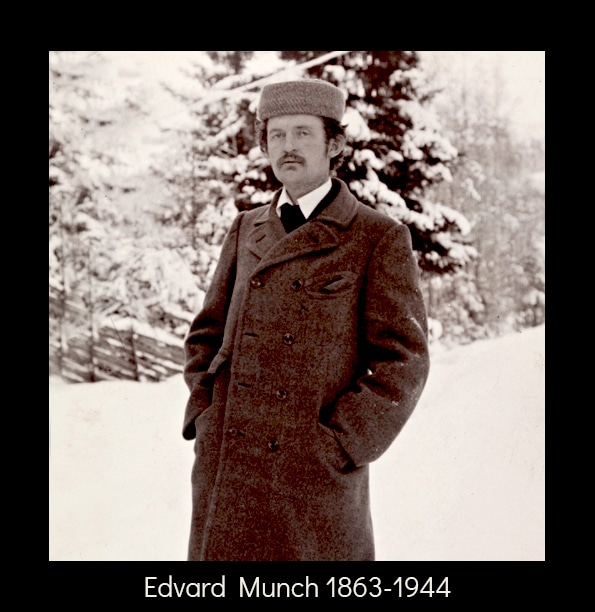

We had a think about Edvard Munch

(Born December 12th 1863 in Löten, Norway and passing January 23, 1944.)

Edvard was a Norwegian painter and printmaker whose work is widely recognised and very intense. We chatted about how great it would have been to have him on board in our fine art print studio. We specifically thought about his painting The Scream, or The Cry (1893), which has been described as a symbol of modern spiritual anguish.

Right now as everyone deals with complex inner turmoil and mixed economic and personal anxiety brought to them with this pandemic, triggered by the social distancing requirements many communities and individuals find themselves placed under, more than ever, Edvards’ work resonates deeply with us.

In addition to The Scream , The Kiss & Consolation, both highlight the profound longing for comfort and healing through physical touch. All human beings and animals share the longing for touch and for many elderly or singletons living alone through this pandemic, it now is a needed part of our social repertoire which is sadly missing.

In his early years Edvards mother died when he was 5 years old, followed by the death of his sister Sophie when he was in his teens: neither experience bares thinking about, especially during such delicate and young character forming ages. That unfortunately wasn’t the end for him, only the beginning in his personal journey through deep spiritual darkness. Edvard’s sister Laura, four years his junior, developed a schizoaffective illness during her adolescence and required intermittent lifelong hospitalizations for mental illness, such torture for her to experience and it must have been hell for Edvard to think about his sibling, her lack of freedom and her mental decline when he had no ability to help or rescue her from such ill fate.

Later on, his only brother Peter died at the young age of 30 from pneumonia. To say Edward was plagued by death and disease is an understatement.

In 1892 Edwards father died and he decided to base himself mainly in France and was funded by state scholarships. He embarked on the most productive, as well as the most troubled, period of his artistic life. During this period he produced the series named "Frieze of Life," including titles "Despair" (1892), "Melancholy" (c. 1892–93), "Anxiety" (1894), "Jealousy" (1894–95) and "The Scream" (1893), also known as "The Cry".

With all these paintings he exposes himself in his work, which utterly arrests you on first glance. Every title from the series draws in millions of art lovers worldwide. Every time you look at “The Scream” you see nothing and you feel everything. You feel his deep unadulterated despair. It’s a profound piece of work and comes as no surprise that A new Guinness World Record has been set for the most expensive painting sold at auction It took only 12 minutes to sell his 1895 pastel of “The Scream” going under the hammer at $119.9 million, to become the world’s most expensive work of art ever to sell at auction.

Edwards’s work is raw and you see how he threw his whole soul into his work with full transparency, for most of us who admire his work, it’s priceless.

After the titles from his ‘Frieze of Life’ series were loved by the arts scene he enjoyed the success of that for a while but he also loved a drink and he drank in excess, we imagine he was trying unsuccessfully to suppress his inner demons, as so many people do. Unfortunately he lost the plot and in 1908, he started hearing voices, suffering from paralysis on one side, collapsed and had to check himself into a private sanitarium.

We all will be having moments of temporary insanity but nothing like Edwards experience. We can all feel the true meaning of privilege also as we experience the effects of COVID-19 dependent on our particular country of residence and our personal socio- economic position; these factors define our journey through this pandemic as it would have defined Edvard’s journey through his life in relative poverty growing up. In his later life, after his success he could afford private health care and that was a small privilege that helped him survive.

There are an unfortunate ‘many’ who are forced to live in squalor, in confinement and unhygienic cold and barren dwellings. Having lost all their belongings, they must feel they are loosing their minds as they are herded to atrocious camps made for the displaced, often fit for animals, not humans. After fleeing for their lives, escaping war, carrying their children for miles barefoot, injured and not knowing where their next glass of clean water will come from, they are faced with utterly devastating and archaic shelters with less than basic facilities, and little safety.

This is a modern day tragedy we all feel happening around us every day, it comes closer and closer towards our doorsteps and it becomes harder and harder to ignore. Different governments try close borders, try to put a lid on increased immigration, which is an unstoppable force, they turn their back on global love, choosing disaster capitalism instead.

Back in Edwards day tuberculosis was a tragedy of it’s time, raging, misunderstood and widespread. Both Edwards mother and sister died of tuberculosis and in the 19th century the mortality rate among young and middle-aged adults was high. What was interesting was the surge of Romanticism, which stressed feeling over reason, lots of people referred to the disease tuberculosis as the "Romantic disease".

Right now we observe a strange kind of romanticism as people are contending with the question of ‘feeling over reason’: artists trying to process the new world in isolation, the societal changes in hand, relationships, internal spiritual questions and their work.

During the 19 century tuberculosis was dubbed the White Plague, mal de vivre, and mal du siècle. Suffering from TB was thought to bestow upon the sufferer-heightened sensitivity. The disease unlike COVID-19 progressed slowly and allowed for a so-called "good death". Sufferers found they had time to sort things out and arrange all their affairs. One of the saddest things about COVID-19 is the idea of anyone dying, whilst looking into the eyes of a stranger wearing a mask. An eerie thought for anyone to have to face.

However, one of the greatest things about this pandemic is how it is granting so many people the opportunity to address what is important to them. This pandemic shows us all how fragile life is, how very short, pretty beautiful it is and how it is there for the taking, if we want to grab it and live to our fullest potential, we can.

Whilst people work remotely, lots of people are managing to undertake all the DIY jobs they had left for ‘next bank holiday’ People are finding time to rearrange their internal affairs, and touch base with themselves. People are slowing down to a more manageable pace and understanding the value of spiritual, physical and creative wellbeing.

Back in Edwards day tuberculosis began to represent spiritual purity and temporal wealth, which is fascinating and shows us how the mind can adjust and interpret any situation in surprising ways. Young, ‘upper-class’ women purposefully made their skin appear paler to achieve the consumptive appearance. The poet Byron wrote, "I should like to die from consumption", and this helped popularize the disease also referred to as “the disease of artists”.

After this he drank much less, got his head together as much as possible and in the spring of 1909, he managed to check out. Edvard was eager to get back to work and back to success but most of his great works were behind him.When the work is spewing out without thought or intention, it is often the case that that the work is great. Success can alter a path with it’s calling to look out, rather than within.

Free and beautifully violent work is too hard to control, has a life of it’s own and won’t succumb to any such callings. Art is a beast within, raging and pushing against an artists’ soul until either it bursts out and is released, or eats the artist alive.

So many creative humans are out there, living in isolation trying to record their experiences, trying to clamber onto their small stage to be seen and heard whilst the doors of society are closed. This is a greater opportunity to lock in and see what occurs naturally.

Edvard had a relationship with a businessman/art dealer, Rolf Stenersen, who wrote his biography at Munch's request, entitled Edvard Munch: Closeup of a Genius.Rolf said that later in his life Edvard developed a very intense relationship with his paintings and actually talked about them as if they were living people. When he was offered a large amount of money for a painting he did not want to part with, he said, "I must have some of my friends on the walls." Edward nearly died of influenza in the pandemic of 1918-19, but recovered, he painted right up to his death.

The morning Edvard died he was living in a country house in Ekely near Oslo.

He was painting his old friend Hans Jaeger who had passed 30 years before him. They had spent time together in their bohemian days and it’s nice to think of them in that moment connected again as friends in his last hours as an artist, living in isolation.

Edward Munch died at home on January 23, 1944.

We love his work, his work touches us and we celebrate his work in our cult collection.

We have some work where the proceeds go towards helping the frontline staff in the crisis. We have some extraordinary new emerging artists showcasing their work in the gallery and we continue to be inspired by them baring their soul for the world to see.

Mikkel Ullah says it best. "Revive your optimism"

We hope this experience bequeaths us all a new skin and shines fresh light on all people.

To all established and emerging artists worldwide trying to make art and trying to make it through to the other side; we’ll see you there.

Love

P.G.